Bruce Riedel Reveals the Failed CIA Operations in Tibet

U.S. President John F. Kennedy faced two great crises in 1962 – the Cuban missile crisis and the Sino-Indian War. While his part in the missile crisis that threatened to snowball into a nuclear war has been thoroughly studied, his critical role in the Sino-Indian War has been largely ignored. Bruce Riedel fills that gap with JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and the Sino-Indian War. Riedel’s telling of the president’s firm response to China’s invasion of India and his deft diplomacy in keeping Pakistan neutral provides a unique study of Kennedy’s leadership. Embedded within that story is an array of historical details of special interest to India, remarkable among which are Jacqueline Kennedy’s role in bolstering diplomatic relations with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan President Ayub Khan, and the backstory to the China-India rivalry – what is today the longest disputed border in the world.

In my analysis, the climax of CIA’s covert Tibet operation was the Tibetan Uprising of 1959. Its failure culminated in the India-China War of 1962. The Crisis during the presidency of John F. Kennedy was the direct result of CIA’s miscalculation of the Enemy’s intelligence and military capabilities and making false assumptions about the Enemy’s intentions.

Bruce Riedel is senior fellow and director of the Brookings Intelligence Project. He joined Brookings following a thirty-year career at the CIA. His previous books include The Search for al Qaeda: Its Leadership, Ideology, and Future; Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America, and the Future of the Global Jihad; and Avoiding Armageddon: America, India, and Pakistan to the Brink and Back.

The great conspiracy hatched by the UK and the US to dismember India in 1947 is not mentioned in JFK’s Forgotten Crisis Book Review. The First Kashmir War of 1947-48 is not because of Nehru’s incompetence. Following this unfair and unjust attack on India in 1947, Nehru acted in the interests of India and obtained the Soviet support for Kashmir without any concern for his own policy of Non-Alignment. He was indeed a great diplomat who performed a balancing act. The Communist takeover of mainland China and Chairman Mao Zedongs’s Expansionist Doctrine compelled Nehru to visit Washington D.C. in 1949 to initiate the Tibetan Resistance Movement and Nehru kept it as a covert operation to avoid provoking the Soviets. Nehru offered the UN Security Council seat to Red China to please the Soviets for they are the only people who fully supported India on the Kashmir issue.

It is the US policy which helped Red China to occupy Aksai Chin area of Ladakh. The US claims Kashmir as the territory of Pakistan. Even today, the official maps of the US show Kashmir as Pakistan’s territory and the US continues to support Pakistan with an aim to dismember India. These covert operations have extended to Punjab and to the Northeast.

Nehru kept his cool and obtained the US support to defend the Northeast Frontier. Kennedy did not hesitate to use the Nuke threat and it forced Red China to declare unilateral ceasefire. India regained the full control of the Northeast Frontier while the Chinese still occupy Ladakh which clearly reveals the nature of the US policy which does not recognize India’s right to Kashmir.

Too much attention is given by Indian readers to Mrs. Kennedy’s sleeping arrangements during her visit to New Delhi in March 1962. She came with two other ladies. I know the man who cleans the trash cans of that suite. She was experiencing her monthly period during her stay in New Delhi. Nehru may wear a Red Rose but he was not fond of mating women during their monthly periods. Feel free to ask the CIA or Bruce Riedel to refute my account. The evidence is in the trash can, the dust bin called History.

All said and done, the CIA failed in 1959 for they underestimated the capabilities of the Enemy in Tibet. The Tibet Uprising of 1959 was brutally crushed and CIA helped the Dalai Lama to find shelter in India. The CIA again failed in Cuba for they underestimated the capabilities of the Enemy in Cuba. Basically, the CIA lacks intelligence capabilities and gave false assurances to Nehru about China’s intentions and preparedness to wage a war across the Himalayan Frontier. Ask Chairman Mao Zedong as to why he attacked India in 1962. What did he say about his own attack?

Indians keep repeating the false narrative shared by Neville Maxwell, a communist spy. What about Indian Army Chief? What was his name? Was he related to Nehru clan? Who appointed him to that position? Was there any favoritism? India honored all the military leaders who defended Kashmir.

Tell me about the Battlefield casualties. How many killed and wounded during the 1962 War? Ask Red China to give me its numbers. What is the secret about it? Ask Red China to declassify its War Record to get a perspective on the Himalayan Blunders of Nehru.

Whole Review – JFK’s Forgotten Crisis, Book by Bruce Riedel. On behalf of Special Frontier Force – Vikas Regiment, I reject Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s interpretation of Prime Minister Nehru’s Policy since 1947.

Rudra Rebbapragada

Special Frontier Force/Establishment 22/Vikas Regiment

The Himalayan Blunders of Nehru

As Stated In ‘JFK’s Forgotten Crisis’

Jaideep A Prabhu

Feb 06, 2025,

https://swarajyamag.com/books/the-failure-of-nehru-the-initiative-of-jfk

PM Modi urged the MPs to read ‘JFK’s Forgotten Crisis’ in his Parliament speech.

JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and the Sino-Indian War, Bruce O. Riedel, Brookings Institution, 2015

Bruce Riedel’s book is written in an accessible style and adds considerably to our understanding of the limitations of Nehru, the India-friendliness of JFK, and the Sino-Indian War of ’62.

Occurring in the shadows of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Sino-Indian War of 1962 is a forgotten slice of history that is remembered vividly only in India.

With it is buried an important episode of US president John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s diplomacy, an intriguing ‘what-if’ of Indo-US relations, and perhaps the most active chapter in the neglected history of Tibet’s resistance to China’s brutal occupation.

The war, however, brought about significant geopolitical changes to South Asia that shape it to this day. Bruce Riedel’s JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and the Sino-Indian War is a gripping account of the United States’ involvement in South Asia and Kennedy’s personal interest in India.

In it, he dispels the commonly held belief that India was not a priority of US foreign policy in the early 1960s and that Kennedy was too preoccupied with events in his own backyard to pay any attention to a “minor border skirmish” on the other side of the world.

Except perhaps among historians of the Cold War, it is not widely known that the United States cosied up to Pakistan during the Eisenhower administration not to buttress South and West Asia against communism but to secure permission to fly reconnaissance missions into the Soviet Union, China, and Tibet.

Initiated in 1957, the US-Pakistan agreement allowed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to operate U-2 reconnaissance planes from Lahore, Peshawar, and other airbases in West Pakistan over Communist territory. Airfields in East Pakistan, such as at Kurmitola, were also made available to the United States. Some of the missions were flown by the Royal Air Force as well.

These overflights provided a wealth of information about the Soviet and Chinese militaries, economies, terrain, and other aspects important to Western military planners. Particularly useful was the information on China, which was otherwise sealed off to Western eyes and ears.

Ayub Khan, the Pakistani president, claimed his pound of flesh for the agreement – Washington and Karachi signed a bilateral security agreement supplementing the CENTO and SEATO security pacts that Pakistan was already a member of and American military aid expanded to include the most advanced US jet fighter of the time, the F-104.

In addition to intelligence gathering, the United States was also involved – with full Pakistani complicity – in supporting Tibetan rebels fight the Chinese army.

The CIA flew out recruits identified by Tibetan resistance leaders, first to Saipan and then on to Camp Hale in Colorado or to the Farm – the CIA’s Virginia facility – to be trained in marksmanship, radio operations, and other crafts of insurgency. The newly-trained recruits were then flown back to Kurmitola, from where they would be parachuted back into Tibet to harass the Chinese military.

No one in Washington had any illusion that these rebels stood any chance against any professionally trained and equipped force, especially one as large as the People’s Liberation Army, but US policymakers were content to harass Beijing in the hope of keeping it off balance.

Jawaharlal Nehru knew of US activities in Tibet, for his Intelligence Bureau chief, BN Mullick, had his own sources in Tibet. It is unlikely, however, that he knew of Pakistan’s role in the United States’ Tibet operations.

In any case, Nehru did not believe that it was worth antagonising the Chinese when there was no hope of victory; India had to live in the same neighbourhood and hence be more cautious than the rambunctious Americans.

Furthermore, it was the heyday of non-alignment and panchsheel, and the Indian prime minister did not wish to upset that applecart if he could help it. In fact, Nehru urged US President Dwight Eisenhower during their 1956 retreat to the latter’s Gettysburg farmhouse to give the UN Security Council seat held by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist China to Mao Zedong’s Communist China.

As Nehru saw it, a nation of 600 million people could not be kept outside the world system for long, but Ike, as the US president was known, still had bitter memories of the Chinese from Korea fresh in his mind. Yet three years later, when Ike visited India and Chinese perfidy in Aksai Chin had been discovered, the Indian prime minister’s tone was a contrast.

To most, Cuba defines the Kennedy administration: JFK had got off to a disastrous start in his presidency with the Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba, an inheritance from his predecessor’s era.

His iconic moment, indisputably, came two years later in the showdown with Nikita Khrushchev over Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Less well known is the president’s interest in South Asia and India in particular.

Riedel explains how, even before assuming the presidency, Kennedy had made a name for himself in the US Senate with his powerful speeches on foreign policy.

In essence, he criticised the Eisenhower government for its failure to recognise that the era of European power was over; Kennedy wanted to fight a smarter Cold War, embracing the newly liberated peoples of Asia and Africa and denying the Communists an opportunity to fan any residual anti-imperialism which usually manifested itself as anti-Westernism.

Riedel points to a speech in May 1959 as a key indicator of the future president’s focus:

In May 1959, JFK declared, “…no struggle in the world today deserves more of our time and attention than that which now grips the attention of all Asia. That is the struggle between India and China for leadership of the East…” China was growing three times as fast as India, Kennedy went on, because of Soviet assistance; to help India, the future president proposed, NATO and Japan should put together an aid package of $1 billion per year that would revitalise the Indian economy and set the country on a path to prosperity.

The speech had been partially drafted by someone who would also play a major role in the United States’ India policy during Kennedy’s presidency: John Kenneth Galbraith.

Riedel shows how, despite his Cuban distraction, Kennedy put India on the top of his agenda. A 1960 National Intelligence Estimate prepared by the CIA for the new president predicted a souring of India-China relations; it further predicted that Delhi would probably turn to Moscow for help with Beijing.

However, the border dispute with the Chinese had shaken Nehru’s dominance in foreign policy and made Indian leaders more sympathetic of the United States. The NIE also projected the military gap between India and China to increase to the disadvantage of the former.

The PLA had also been doing exceedingly well against Tibetan rebels, picking them off within weeks of their infiltration. By late 1960, a Tibetan enclave had developed in Nepal; Mustang, the enclave was called, became the preferred site for the CIA to drop supplies to the rebels.

Galbraith, the newly appointed ambassador to India, disapproved of the CIA’s Tibetan mission, which had delivered over 250 tonnes of arms, ammunition, medical supplies, communications gear, and other equipment by then.

Like Nehru, he thought it reckless and provocative without any hope of achieving a favourable result. There were, however, occasional intelligence windfalls coming from Tibet and Kennedy overruled Galbraith for the moment.

JFK’s Forgotten Crisis shows how Galbraith was far more attuned to India than he is usually given credit for. He is most famously remembered – perhaps only among Cold War historians – for nixing a Department of Defence proposal in 1961 that proposed giving India nuclear weapons.

Then, he predicted – most likely accurately – that Nehru would denounce such an offer and accuse the United States of trying to make India its atomic ally. Now, the Harvard professor pushed for Nehru and Kennedy to meet.

This would give the Indian prime minister, Galbraith hoped, an opportunity to remove any lingering suspicions he may have had about US foreign policy in South Asia. The large aid package Washington had planned for India would only sweeten the meeting.

This was not to be: Nehru remained most taciturn and almost monosyllabic during his visit to Jacqueline Kennedy’s home in Newport. However, he was quite enamoured by the First Lady, and Jackie Kennedy later said that she found the Indian leader to be quite charming; she, however, had much sharper things to say about the leader’s daughter!

Washington’s outreach to Delhi annoyed Karachi. Though ostensibly the US-Pakistan alliance was to fight communism, the reality was that Pakistan had always been preoccupied with India.

Ayub Khan felt betrayed that the United States would give India, a non-aligned state, economic assistance that would only assist it in developing a stronger military to be deployed against Pakistan. Riedel’s account highlights the irresistible Kennedy charm – when Pakistan suspended the Dragon Lady’s flights from its soil, JFK was able to woo Khan back into the fold.

However, the Pakistani dictator had a condition – that Washington would discuss all arms sales to India with him. This agreement would be utterly disregarded during the Sino-Indian War and Pakistan would start looking for more reliable allies against their larger Hindu neighbour.

Riedel reveals how Pakistan had started drifting into the Chinese orbit as early as 1961, even before China’s invasion of India, an event commonly believed to have occurred after India’s Himalayan humiliation.

When India retook Goa from the Portuguese, a NATO country, it caused all sorts of difficulties for the United States.

On the one hand, Kennedy agreed with the notion that colonial possessions should be granted independence or returned to their original owners but on the other, Nehru and his minister of defence, Krishna Menon, had not endeared themselves to anyone with their constant moralising; their critics would not, now, let this opportunity to call out India’s hypocrisy on the use of force in international affairs pass.

The brief turbulence in relations was set right, oddly, by the First Lady again. On her visit to India, she again charmed the prime minister and he insisted that he stay with him instead of the US embassy and had the room Edwina Mountbatten had often used on her visits readied. The play of personalities, an often ignored facet of diplomacy, has been brought out well by Riedel.

Too much attention is given by Indian readers to Mrs. Kennedy’s sleeping arrangements during her visit to New Delhi in March 1962. She came with two other ladies. I expect Intelligence analysts to give attention to the US Kashmir Policy rather than speculating about the First Lady’s Charm Offensive. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s (JBK) trip to India and Pakistan: New Delhi, Delhi, India, fashion show at Cottage Industries Emporium

Please credit “Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston”

Ironically, China believed that the Tibetan resistance movement was being fuelled by India with US help. India’s granting of asylum to the Dalai Lama did not help matters either, even though it was Nehru who had convinced the young Dalai Lama to return to Tibet in 1956 and have faith in Beijing’s promises of Tibetan autonomy.

Although Indian actions did factor into the Chinese decision to invade India in October 1962, records from Eastern European archives indicate that the Sino-Soviet split was also partly to blame. Humiliating India served two purposes for Mao: first, it would secure Chinese access to Tibet via Aksai Chin, and second, it would expose India’s Western ties and humiliate a Soviet ally, thereby proclaiming China to be the true leader of the communist world.

Riedel’s treatment of the war and the several accounts makes for interesting reading, though his belief that there is rich literature on the Indian side about the war is a little puzzling.

Most of what is known about the Sino-Indian War comes from foreign archives – primarily the United States, Britain, and Russia but also European archives as their diplomats recorded and relayed to their capitals opinions they had formed from listening to chatter on the embassy grapevine.

There is, indeed, literature on the Indian side but much of it seeks to apportion blame rather than clarify the sequence of events. Records from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of External Affairs, or the Ministry of Defence are yet to be declassified, though the Henderson-Brooks-Bhagat Report was partially released to the public by Australian journalist Neville Maxwell.

Chinese records, though not easily accessible, have trickled out via the most commendable Cold War International History Project. The Parallel History Project has also revealed somewhat the view from Eastern Europe.

Riedel dispels the notion of Nehru’s Forward Policy as the cassus belli. According to Brigadier John Dalvi, a prisoner of war from almost the outset, China had been amassing arms, ammunition, winter supplies, and other materiel at its forward bases since at least May 1962.

This matches with an IB report Mullick had provided around the same time. Furthermore, the Indian forces were outnumbered at least three-to-one all along the border and five-to-one in some places. The troops were veterans of the Korean War and armed with modern automatic rifles as compared to Indian soldiers’ 1895 issue Lee Enfield.

Though Riedel exonerates Nehru on his diplomacy, he does not allow the prime minister’s incompetence to pass: the political appointment of BM Kaul, the absolute ignorance of conditions on the ground, and the poor logistics and preparation of the troops on the border left them incapable of even holding a Chinese assault, let alone breaking it.

JFK’s Forgotten Crisis brings out a few lesser known aspects of the Sino-Indian War. For example, India’s resistance to the PLA included the recruitment of Tibetan exiles to harass the PLA from behind the lines. Nehru was approached by the two men most responsible for the debacle on the border – Menon and Kaul – with the proposal which Nehru promptly agreed.

A team, commanded by Brigadier Sujan Singh Uban and under the IB (Intelligence Bureau, later Research and Analysis Wing or R&AW) was formed. A long-continuing debate Riedel takes up in his work is the Indian failure to use air power during the conflict in the Himalayas.

It has been suggested that had Nehru not been so timid and fearful of retaliation against Indian cities but deployed the Indian air force, India may have been able to repel or at least withstand the Chinese invasion. One wonders how effective the Indian Air Force really might have been given the unprepared state of the Army.

In any case, Riedel points out that the Chinese air force was actually larger than the IAF – the PLAAF had over 2,000 jet fighters to India’s 315, and 460 bombers to India’s 320. Additionally, China had already proven its ability to conquer difficult terrain in Korea.

Throughout the South Asian conflict, the United States was also managing its relationship with Pakistan. Despite the Chinese invasion, the bulk of India’s armies were tied on the Western border with Pakistan and Ayub Khan was making noises about a decisive solution to the Kashmir imbroglio; it was all the United States could do to hold him back.

However, Ayub Khan came to see the United States as a fair-weather friend and realised he had to look elsewhere for support in his ambitions against India: China was the logical choice. Thus, the 1962 war resulted in the beginning of the Sino-Pakistani relationship that would blossom to the extent of Beijing providing Islamabad with nuclear weapon and missile designs in the 1980s.

The Chinese had halted after their explosive burst into India on October 20. For a full three weeks, Chinese forces sat still while the Indians regrouped and resupplied their positions. On November 17, they struck again and swept further south. The Siliguri corridor, or the chicken neck, was threatened , and India stood to lose the entire Northeast.

In panic, Kaul asked Nehru to invite foreign armies to defend Indian soil. A broken Nehru wrote two letters to Washington on the same day, asking for a minimum of 12 squadrons of jet fighters, two B-47 bomber squadrons, and radar installations to defend against Chinese strikes on Indian cities.

These would all be manned by American personnel until sufficient Indians could be trained. In essence, India wanted the United States to deploy over 10,000 men in an air war with China on its behalf.

There is some doubt as to what extent the United States would have gone to defend India. However, that November, the White House dispatched the USS Kitty Hawk to the Bay of Bengal (she was later turned around as the war ended).

After the staggering blows of November 17, the US embassy, in anticipation of Indian requests for aid, had also started preparing a report to expedite the process through the Washington bureaucracy.

On November 20, China declared a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew its troops to the Line of Actual Control. A cessation of hostilities had come on Beijing’s terms, who had shown restraint by not dismembering India.

Riedel makes a convincing case that Kennedy would have defended India against a continued Chinese attack had one come in the spring of the following year, and that overt US support may have influenced Mao’s decision.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the United States sent Averell Harriman of Lend-Lease fame to India to assess the country’s needs. Washington had three items on its agenda with India:

1. Increase US economic and military aid to India;

2. Push India to negotiate with Pakistan on Kashmir as Kennedy had promised Ayub Khan; and

3. Secure Indian support for the CIA’s covert Tibetan operations.

The first met with little objection, and though Nehru strongly objected to talks with Pakistan, he obliged. Predictably, they got to nowhere. On the third point, Riedel writes that India agreed to allow the CIA to operate U-2 missions from Char Batia.

This has usually been denied on the Indian side though one senior bureaucrat recently claimed that Nehru had indeed agreed to such an arrangement but only two flights took off before permission was revoked.

Nonetheless, the IB set up a Special Frontier Force of Tibetans in exile and the CIA supported them with equipment and air transport from bases in India. All this, however, withered away as relations again turned sour after the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 and the election of Richard Nixon.

Most of the sources JFK’s Forgotten Crisis uses are memoirs and prominent secondary sources on South Asia and China. Riedel also uses some recently declassified material from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library that sheds new light on the president’s views on South Asia.

Despite the academic tenor of the book, it is readily accessible to lay readers as well; personally, I would have preferred a significantly heavier mining of archival documents and other primary sources but that is exactly what would have killed sales and the publisher would not have liked!

Overall, Riedel gives readers a new way to understand the Kennedy years; he also achieves a fine balance in portraying Nehru’s limitations and incompetence. The glaring lack of Indian primary sources also reminds us of the failure of the Indian government to declassify its records that would inform us even more about the crisis.

As Riedel notes, the Chinese invasion of India created what they feared most and had not existed earlier: the United States and India working together in Tibet. This was largely possible also because of the most India-friendly president in the White House until then.

Yet Pakistan held great sway over American minds thanks to the small favours it did for the superpower. It was also the birth of the Sino-Pakistani camaraderie that is still going strong. The geopolitical alignment created by the Sino-Indian War affects South Asian politics to this day. Yet it was a missed opportunity for Indo-US relations, something that had to await the presidency of George W. Bush.

There are two things Indian officials would do well to consider.

First, Pakistan’s consistent ability to extract favours from Washington is worth study: if small yet important favours can evince so much understanding from the White House, it would be in Indian interests to do the same.

Second, Jaswant Singh’s comment to Strobe Talbott deserves reflection: “Our problem is China, we are not seeking parity with China. we don’t have the resources, and we don’t have the will.” It is time to develop that will.

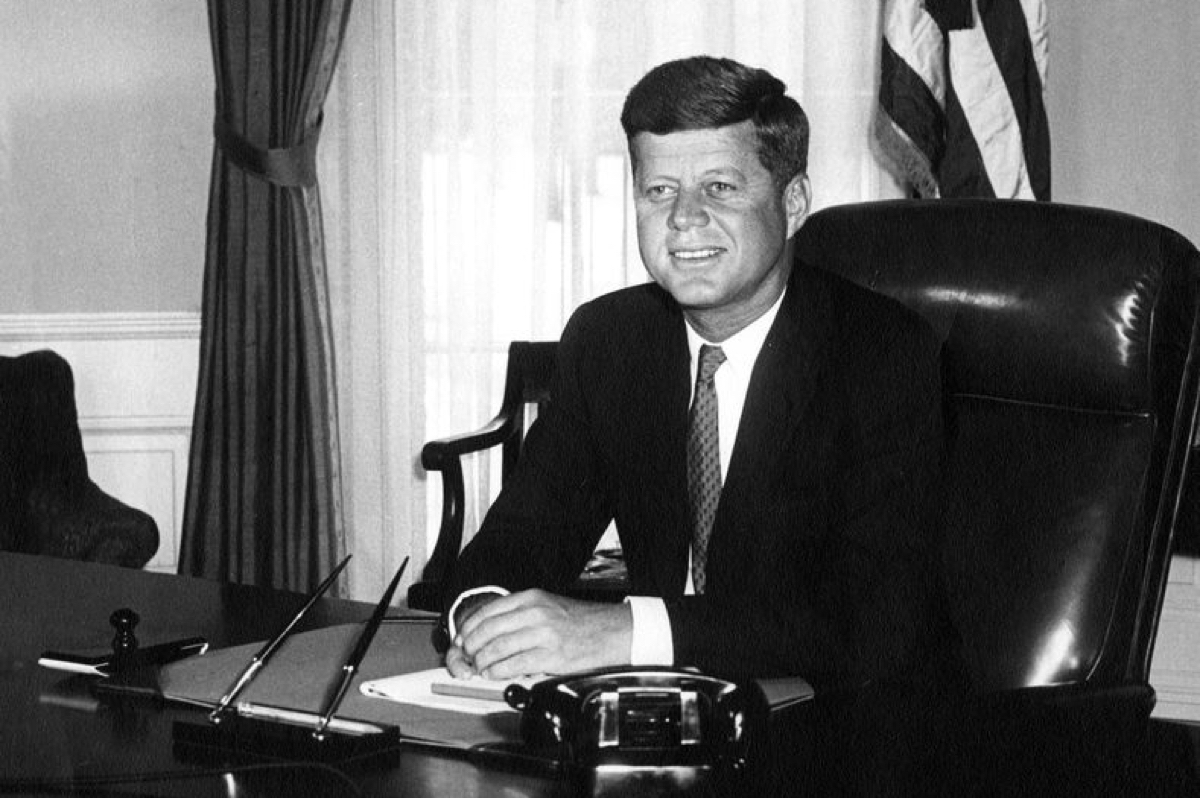

Special Frontier Force Pays Tribute to President John F. Kennedy

While sharing an interesting story titled Cold War Camelot published by The Daily Beast which includes excerpts from the book JFK’s Forgotten CIA Crisis by Bruce Riedel, I take the opportunity to pay tribute to President John F. Kennedy for supporting the Tibetan Resistance Movement initiated by President Dwight David Eisenhower. Both Tibet, and India do not consider Pakistan as a partner in spite of the fact of Pakistan permitting the use of its airfields in East Pakistan. Red China has formally admitted that she had attacked India during October 1962 to teach India a lesson and to specifically discourage India from extending support to Tibetan Resistance Movement. Red China paid a huge price. She is not able to truthfully disclose the human costs of her military aggression in 1962. She failed to achieve the objectives of her 1962 War on India. President Kennedy threatened to “Nuke” China and forced her to declare unilateral cease-fire on November 21, 1962. China withdrew from territories she gained using overwhelming force. People’s Liberation Army (PLA) sustained massive casualties and their brief victory over India did not give them any consolation.

Red China’s 1962 misadventure forged a stronger bonding between Tibet, India, and the United States. The 1962 War does not provide legitimacy to Communist China’s occupation of Tibet.

On behalf of Special Frontier Force, I feel honored to share John F Kennedy’s Legacy. Due to Cold War Era secret diplomacy, Kennedy’s role in Asian affairs is not fully appreciated both in the US and India. In 1962, during the presidency of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the second President of Republic of India, Kennedy joined hands with India and Tibet to transform the Tibetan Resistance Movement into a regular fighting force.

Special Frontier Force, a military organization in India was established during the Cold War Era while the US fought wars in the Korean Peninsula and Vietnam. In my view, Special Frontier Force is the relic of Unfinished Vietnam War, America’s War against the spread of Communism in South Asia.

Cold War Camelot

Bruce Riedel

11.08.1512:01 AM ET

JFK’s Forgotten CIA Crisis

During a spectacular dinner at Mount Vernon, Kennedy pressed Pakistan’s leader for help with a sensitive spy operation against China.

At Mount Vernon

The magic of the Kennedy White House, Camelot, had settled in at Mount Vernon. It was a dazzling evening, a warm July night, but a cool breeze came off the Potomac River and kept the temperature comfortable. It was Tuesday, July 11, 1961, and the occasion was a state dinner for Pakistan’s visiting president, General Ayub Khan, the only time in our nation’s history that George Washington’s home has served as the venue for a state dinner.

President John F. Kennedy had been in office for less than six months, but his administration had already been tarnished by the failed CIA invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs and a disastrous summit with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, Austria. Ayub Khan wrote later that the president was “under great stress.” The Kennedy administration was off to a rocky start: It needed to show some competence.

The idea of hosting Ayub Khan at Mount Vernon came from Kennedy’s wife, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, who was inspired by a dinner during the Vienna summit held a month earlier at the Schönbrunn Palace, the rococo-style former imperial palace of the Hapsburg monarchy built in the seventeenth century. Mrs. Kennedy was impressed by the opulence and history displayed at Schönbrunn and at a similar dinner held on the same presidential trip at the French royal palace of Versailles. America had no royal palaces, of course, but it did have the first president’s mansion just a few miles away from the White House on a bluff overlooking the Potomac River. The history of the mansion and the fabulous view of the river in the evening would provide a very special atmosphere for the event.

On June 26, 1961, the First Lady visited Mount Vernon privately and broached the idea with the director of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, which manages the estate. It was a challenging proposal. The old mansion was too small to host an indoor dinner so the event would have to take place on the lawn. The mansion had very little electricity in 1961 and was a colonial antique, without a modern kitchen or refrigeration, so that the food would have to be prepared at the White House and brought to the estate and served by White House staff. But the arrangements were made, with the Secret Service and Marine Corps providing security, and the U.S. Army’s Third Infantry Regiment from Fort Myers providing the colonial fife and drum corps for official presentation of the colors. The National Symphony Orchestra offered the after-dinner entertainment. Tiffany and Company, the high-end jewelry company, provided the flowers and decorated the candlelit pavilion in which the guests dined.

The guests arrived by boat in a small fleet of yachts led by the presidential yacht, Honey Fitz, and the secretary of the navy’s yacht, Sequoia. They departed from the Navy Yard in Washington and sailed the fifteen miles down river to Mount Vernon past National Airport and Alexandria, Virginia; the trip took an hour and fifteen minutes. On arrival the most vigorous guests, such as the president’s younger brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, climbed the hill to the mansion on foot, but most took advantage of the limousines the White House provided.

Brookings Institution

The guest list was led by President Ayub Khan and his daughter, Begum Nasir Akhtar Aurangzeb, and included the Pakistani foreign minister and finance minister, as well as Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States, Aziz Ahmed, and various attaches from the embassy in Washington. Initially the ambassador was upset that the dinner would not be in the White House, fearing it would be seen as a snub. The State Department convinced Ahmed that having it at Mount Vernon was actually a benefit and would generate more publicity and distinction.

The Americans invited to the dinner were the elite of the new administration. In addition to the president, attorney general, and vice president and their wives, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Secretary of the Navy John Connally, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Lyman Lemnitzer, and their wives joined the party. Six senators, including J. W. Fulbright, Stuart Symington, Everett Dirksen, and Mike Mansfield were joined by the Speaker of the House and ten congressmen, including a future president, Gerald Ford, and their wives. The U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, William Roundtree; the chief of the United States Air Force, General Curtis Lemay; Assistant Secretary of State Phillip Talbott; Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver; and the president’s military assistant, Maxwell Taylor, were also in attendance. Walter Hoving, chairman of Tiffany, and Mrs. Hoving, and a half-dozen prominent Pakistani and American journalists, such as NBC correspondent Sander Vanocur, attended from outside the government. In total more than 130 guests were seated at sixteen tables.

Perhaps the guest most invested in the evening, however, was the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Allen W. Dulles. The Kennedys had long been friends of Allen Dulles. A few years before the dinner Mrs. Kennedy had given him a copy of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novel, From Russia, with Love, and Dulles, like JFK, became a big fan of 007. Dulles was also a holdover from the previous Republican administration. He had been in charge of the planning and execution of the Bay of Pigs fiasco that had tarnished the opening days of the Kennedy administration, but Dulles still had the president’s ear on sensitive covert intelligence operations, including several critical clandestine operations run out of Pakistan with the approval of Field Marshal Ayub Khan.

Before sitting down for dinner just after eight o’clock, the guests toured the first president’s home and enjoyed bourbon mint juleps or orange juice. Both dressed in formal attire for the occasion, Kennedy took Ayub Khan for a walk in the garden alone. At that time, the CIA was running two very important clandestine operations in Pakistan. One had already made the news a year earlier when a U-2 spy plane had been shot down over the Soviet Union by Russian surface-to-air missiles; this plane had started its top-secret mission, called Operation Grand Slam, from a Pakistani Air Force air base in Peshawar, Pakistan. The U-2 shoot down had wrecked a summit meeting between Khrushchev and President Eisenhower in Paris in 1960 when Ike refused to apologize for the mission. The CIA had stopped flying over the Soviet Union, but still used the base near Peshawar for less dangerous U-2 operations over China.

The second clandestine operation also dated from the Eisenhower administration, but was still very much top-secret. The CIA was supporting a rebellion in Communist China’s Tibet province from another Pakistani Air Force air base near Dacca in East Pakistan (what is today Bangladesh). Tibetan rebels trained by the CIA in Colorado were parachuted into Tibet from CIA transport planes that flew from that Pakistani air base, as were supplies and weapons. U-2 aircraft also landed in East Pakistan after flying over China to conduct photo reconnaissance missions of the communist state.

Ayub Khan had suspended the Tibet operation earlier that summer. The Pakistani president was upset by Kennedy’s decision to provide more than a billion dollars in economic aid to India.

Pakistan believed it should be America’s preferred ally in South Asia, not India, and shutting down the CIA base for air drops to Tibet was a quiet way to signal displeasure at Washington without causing a public breakdown in the U.S.-Pakistan relationship. Ayub Khan wanted to make clear to Kennedy that an American tilt toward India at Pakistan’s expense would have its costs. In his memoirs, Khan later wrote that he sought to press Kennedy not to “appease India.”

Before the Mount Vernon dinner, Allen Dulles had asked Kennedy to meet alone with Ayub Khan, thinking that perhaps a little Kennedy charm and the magic of the evening would change his mind. The combination worked; the Pakistani dictator told Kennedy he would allow the CIA missions over Tibet to resume from the Pakistani Air Force base at Kurmitula outside of Dacca.

Ayub Khan did get a quid pro quo for this decision later in his visit: Kennedy promised that, even if China attacked India, he would not sell arms to India without first consulting with Pakistan. However, when China did invade India the following year, Kennedy ignored this promise and provided critical aid to India, including arms, without consulting Ayub Khan, who was deeply disappointed.

The main course for dinner was poulet chasseur served with rice and accompanied by Moët and Chandon Imperial Brut champagne (at least for the Americans), followed by raspberries in cream for dessert. President Kennedy hosted a table at which sat Begum Aurangzeb, who wore a white silk sari. Khan enjoyed the beauty of a Virginia summer evening with America’s thirty-one-year-old First Lady; he sat next to Jackie, who wore a Oleg Cassini sleeveless white organza and lace evening gown sashed at the waist in Chartreuse silk. In his toast the Pakistani leader warned that “any country that faltered in Asia, even for only a year or two, would find itself subjugated to communism.” In turn Kennedy hailed Ayub Khan as the George Washington of Pakistan. After midnight the guests were driven back to Washington down the George Washington Parkway.

The CIA operation in Tibet had its detractors in the Kennedy White House, including Kennedy’s handpicked ambassador to India, John Kenneth Galbraith, who called it “a particularly insane enterprise” involving “dissident and deeply unhygienic tribesmen” that risked an unpredictable Chinese response. However, the operation did produce substantial critical intelligence on the Chinese communist regime from captured documents seized by the Tibetans at a time when Washington had virtually no idea what was going on inside Red China. The U-2 flights from Dacca were even more important to the CIA’s understanding of China’s nuclear weapon development at its Lop Nor nuclear test facility.

But Galbraith was in the end correct to be skeptical. The operation did have an unpredicted outcome: The CIA operation helped persuade Chinese leader Mao Zedong to invade India in October 1962, an invasion that led the United States and China to the brink of war and began a Sino-India rivalry that continues today. It also created a Pakistani-Chinese alliance that still continues. The contours of modern Asian grand politics thus were drawn in 1962.

The dinner at Mount Vernon was a spectacular social success for the Kennedys, although they received some predictable criticism from conservative newspapers over its cost. It was also a political success for both Kennedy and the CIA, keeping the Tibet operation alive. As an outstanding example of presidential leadership in managing and executing covert operations at the highest level of government, it is an auspicious place to begin an examination of JFK’s forgotten crisis.

From JFK’s FORGOTTEN CRISIS: TIBET, THE CIA, AND THE SINO-INDIAN WAR, by Bruce Riedel, Brookings Institution Press, November 6, 2015.

© 2014 The Daily Beast Company LLC

Special Frontier Force Remembers the Legacy of 35th US President

On behalf of Special Frontier Force, I feel honored to share John F Kennedy’s Legacy. Due to Cold War Era secret diplomacy, Kennedy’s role in Asian affairs is not fully appreciated both in the US and India. In 1962, during presidency of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the second President of Republic of India, Kennedy joined hands with India and Tibet to transform the Tibetan Resistance Movement into a regular fighting force.

Special Frontier Force, a military organization in India was established during the Cold War Era while the US fought wars in the Korean Peninsula and Vietnam. In my view, Special Frontier Force is the relic of Unfinished Vietnam War, America’s War against the spread of Communism in South Asia.

Remembering John F. Kennedy’s Legacy on his 100th birthday

Published May 29, 2017

Fox News

In this Feb. 27, 1959 file photo, Sen. John F. Kennedy, D-Mass., is shown in his office in Washington. Monday, May 29, 2017 marks the 100-year anniversary of the birth of Kennedy, who went on to become the 35th President of the United States. (AP Photo, File) (AP 1959)

As Americans celebrate this Memorial Day, they also will remember the life and legacy of President John F. Kennedy who was born 100 years ago this Monday.

While the 35th president left a mixed legacy following his assassination in Dallas in 1963, Kennedy remains nearly as popular today as he did during his time in office, and he arguably created the idea of a president’s “brand” that has become commonplace in American politics.

“President Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy worked hard to construct a positive image of themselves, what I call the Kennedy brand,” Michael Hogan, author of ‘The Afterlife of John Fitzgerald Kennedy: A Biography.’ “And because history is as much about forgetting as remembering, they made every effort to filter out information at odds with that image.”

In commemoration of JFK’s 100th birthday, Fox News has compiled a rundown on the life of the 35th president:

Born on May 29, 1917 in Brookline, Massachusetts to Joseph “Joe” Kennedy and Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald Kennedy.

In 1940, Kennedy graduated cum laude from Harvard College with a Bachelor of Arts in government.

From 1941 to 1945, Kennedy commanded three patrol torpedo boats in South Pacific during World War II, including the PT-109 which was sunk by a Japanese destroyer.

In 1946, Kennedy was elected to Congress for Massachusetts’s 11th congressional district and served three terms.

Elected to the U.S. Senate to represent Massachusetts in 1952.

Kennedy marries Jacqueline Bouvier, a writer with the Washington Times-Herald, in 1953.

Receives the Pulitzer Prize in 1957 for his book “Profiles in Courage.”

Elected President of the United States in 1960, becoming the youngest person elected to the country’s highest office, and the first Roman Catholic president.

He is credited with overseeing the creation and launch of the Peace Corps

Sent 3,000 U.S. troops to support the desegregation of the University of Mississippi after riots there left two dead and many others injured

Approved the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 intending to overthrow Cuban leader Fidel Castro

In 1962, Kennedy oversaw the Cuban Missile Crisis — seen as one of the most crucial periods of the U.S.’s Cold War with the Soviet Union

Signed a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union in July 1963

Asked Congress to approve more than $22 billion for Project Apollo with the goal of landing an American on the moon by the end of the 1960s

Escalated involvement in the conflict in Vietnam and approved the overthrow of Vietnam’s President Ngô Đình Diệm. By the time of the war’s end in 1975, more than 58,000 U.S. troops were killed in the conflict

Assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963

The Associated Press contributed to this report.